What do flower gardens, chests of drawers, chocolate cakes, and global development projects have in common? They all might find their origin in a toolkit! Given the proliferation of kits across industry sectors and everyday experiences, we’d do well to consider what the toolkit does, who it serves and how, and what it says about us.

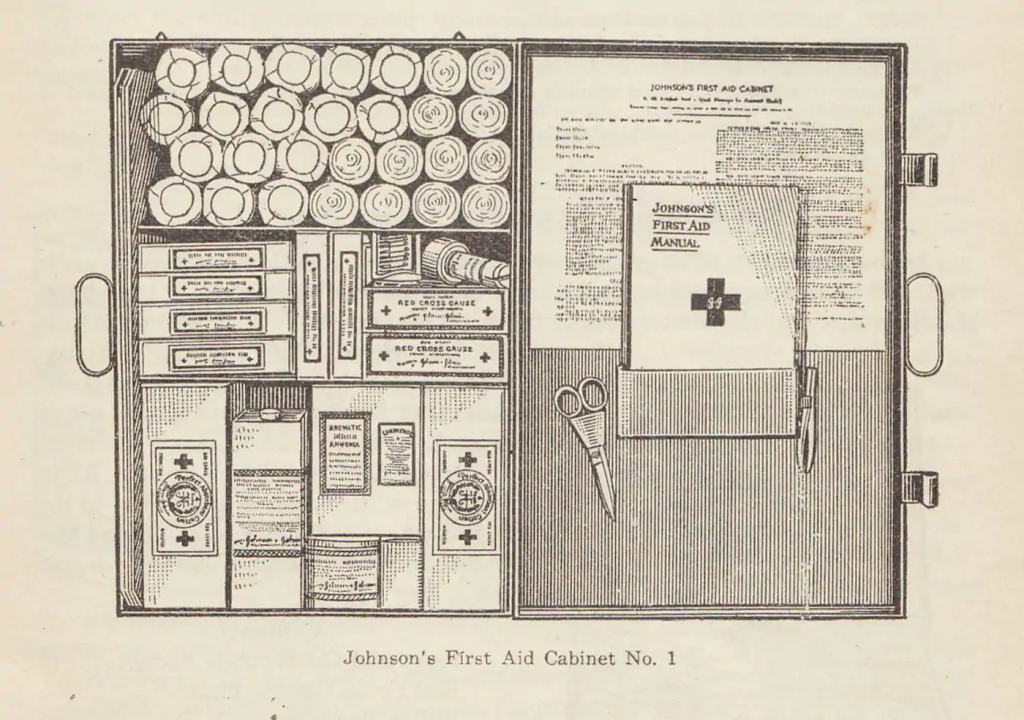

In the 15th century, “kit” denoted a wooden vessel used to hold water, milk, butter, fish, or some other commodity.[1] That vessel came to contain a much greater variety of things. Since the late 19th century, psychiatrists, psychologists, and a fair share of quack diagnosticians have produced kits crammed with puzzles and dolls and flash cards meant to assess intelligence – particularly that of immigrants, in order to determine their potential value to their adopted country.[2] And while psychiatrists were boxing up kits to test the capacities of the mind, Johnson & Johnson was packaging sterile surgical supplies into wooden and metal boxes for use by railway workers engaged in hazardous labor far from medical facilities. The company claims to have created the first First Aid Kit in 1888.[3] Today, you can buy “man kits” full of aftershave, razors, and other potions designed to affirm and enhance your virility. And of course the pandemic precipitated a veritable explosion of kits – from COVID test kits and vaccine supply kits to meal kits and home-school supply kits – that served to minimize our cognitive load and maximize our efficiency.

We need to think about how kits are aesthetic objects that order and arrange things

A kit isn’t just a box of supplies; it’s a judiciously chosen collection of tools and materials designed to script a particular process, aimed to serve a particular purpose (or purposes, plural), and to do so with minimal waste and frustration. Everything a piecework seamstress needed to embroider a lace collar for a wealthy client, or to darn her children’s socks, was right there in her sewing kit. Everything a soldier might need to mend a torn uniform jacket or affix a new insignia, he’d find right there in his own sewing kit, often called, tellingly, a “housewife,” or hussif.[4]

Kits are also sometimes designed to tell a particular story or cultivate a particular identity. Everything a prepper needs to face the apocalypse – a flashlight, a multitool, a hand-crank radio, batteries, matches, water, and so forth – should be right there in his “go bag,” or “bug out bag.”[5] You can also download “Healing Justice Toolkits” and digital literacy toolkits. You can deploy kits to create portable libraries in refugee camps, disaster zones, and underserved urban, rural, and indigenous communities; kits to promote participatory development; and kits to attune us to our relations with microorganisms.[6]

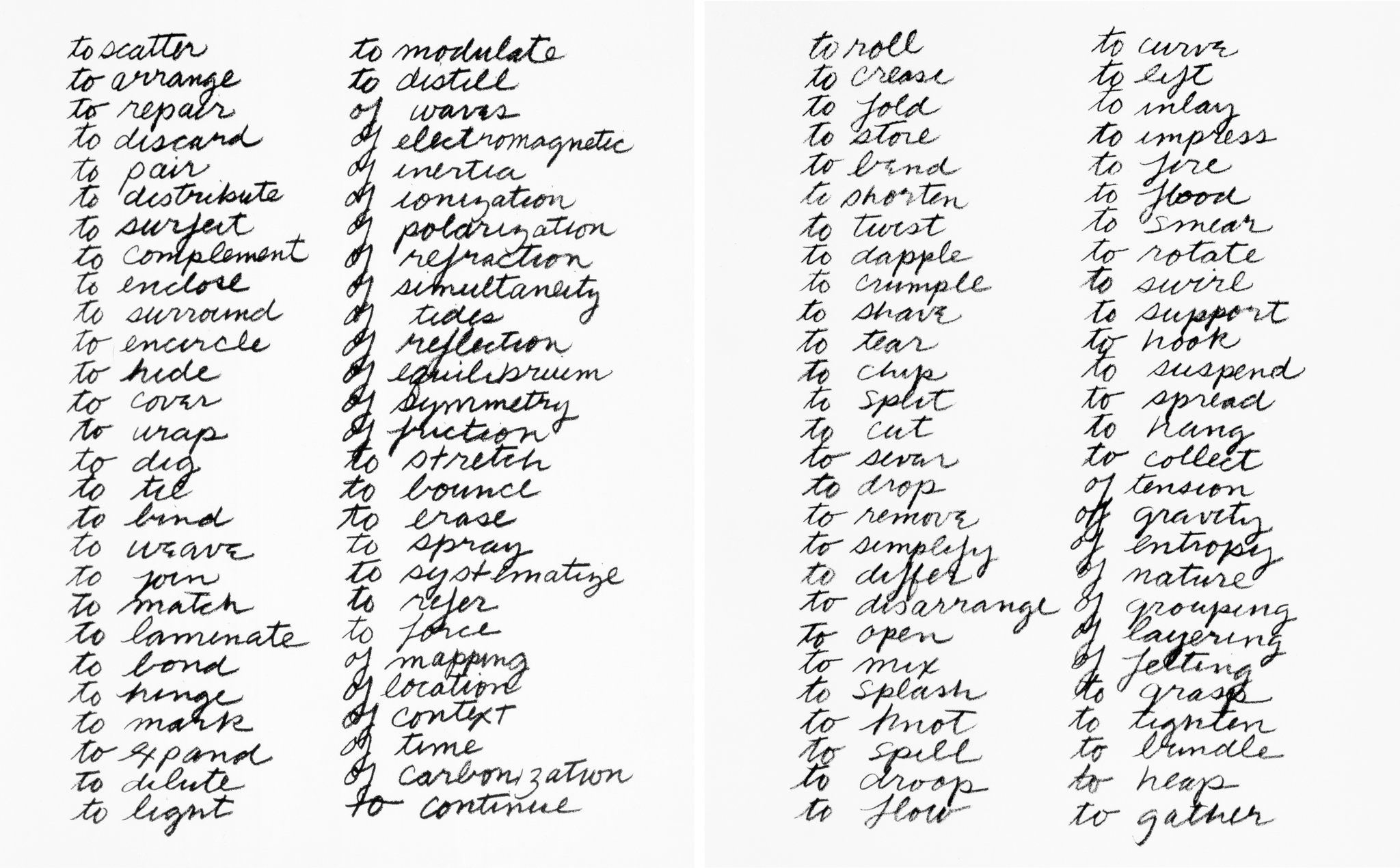

But should you? Is a kit really an appropriate means to effect social justice; to teach students about book-binding or physical computing or, heaven forbid, surgery; to engage marginalized communities in designing their material conditions of living? Especially given the proliferation of kits as methodological and political tools in design and development, we need to think about how kits are aesthetic objects that order and arrange things – and how those aesthetics are rhetorical and epistemological: they make an argument about “best practices,” about what matters, and about how we know things. They interpellate, or summon, particular users and make claims about expertise and whose contributions matter and what knowledge counts. Their component parts shape users’ agency and subjectivity in relation to the objective or purpose at hand – and they have the potential to define that purpose, whether it’s baking a cake or addressing poverty. We need to think about how kits are ontological, too; they constitute a way for tools to be in relation with one another, and for us to be in relation to those tools and to one another, via the toolkit. They also make claims about how the world is put together, and they ostensibly give us the tools to build that world – perhaps a studier, healthier, more just, better designed world. We need to consider how kits model particular politics and ethics, what they are well suited to do, and what possibilities are effectively “boxed out.”

What follows is my own classificatory kit of kits. We start with kits designed for the most rudimentary of purposes: basic survival. We then move on to toolkits as means of inclusion and structures of social relations; then toolkits that facilitate material pedagogy; and, finally, toolkitting as a design method.

TOOLKITTING FOR SURVIVAL

Let’s return to the survivalist kit, whose purported function is nothing short of, well, survival. Yet the kits meant to facilitate this function are more than starkly utilitarian. Geographer and security studies scholar Kezia Barker describes how preppers are aesthetes and improvisatory designers. While they tend to fetishize certain expensive pieces of equipment designed to serve single functions – things like gas masks; customized Land Rovers; and nuclear, biological, and chemical suits, for example – they also value their own agency in designing more quotidian tools – or, if not designing the tools themselves, then designing systems for their collection, organization, and storage. “Prepper social media is filled with photos of equipment, neatly organized in a ‘knolling’ style and often labelled,” Barker writes, “and in endless YouTube videos preppers unpack, display, and talk through their equipment.”[7] Some of Barker’s respondents regarded themselves as part of a “maker” community composed of “really creative people, who are interested in solving problems,” and “some of them [are] just making really beautiful stuff.” Another commented on the value of resourcefulness and modularity: “I now look at things and think, well, that would be a handy material for this, that or [the] other… I’m seeing two or three uses in one item.”[8] Cotton balls soaked in Vaseline can help start a fire. Tampons can double as water-filters. “Across a broad range of forms of consumption,” Barker explains, “items are interrogated for their ability to be attainable, adaptable, replicated, or (multi)functional in future scenarios of infrastructural disconnection.”

Yet embedded in these design values is a troubling blend of ideologies: such technosolutionist libertarianism is rooted in an assumption that kits and skills are more reliable than other people, who are presumably driven primarily by self-interest and will descend into animalistic mob rule when shit hits the fan. Preppers’ characteristic commitment to privatized, commodity-based solutions, whether bunkers or bug-out bags, signals an abandonment of potential collective action or systemic redress; as geographer Bradley Garrett explains, “faith in adaptation” supplants “hope of mitigation.”[9]

Technosolutionist libertarianism is rooted in an assumption that kits and skills are more reliable than other people

In their contribution to the 2014 Istanbul Design Biennial, Tim Parsons and Jessica Charlesworth offered a set of New Survivalism kits that equip subjects aiming to fulfill more than their most basic, functional needs in an apocalypse. The Decision Maker kit comes with an almanac, a copy of the I Ching, sets of Oblique Strategies and Rorschach cards, a tarot deck, and assorted dice to help the user make decisions amidst the pressures of an apocalypse; the Object Guardian kit prepares the user to accession their own material culture collection, just in case museums disappear; and the Futurist Storyteller kit is composed of a set of symbolic objects meant to trigger memories and fantasies, to allow the user to imagine a future despite the hopelessness of the present. With the Rewilder kit, one can train himself, with drug therapies and exercise equipment, to become a hunter gatherer who eventually has no need for a survival kit; he’s primed to see his own body and all that surrounds him in the natural and built world – rocks, branches, bricks – as the ur-toolkit.[10] With their playfulness and absurdity, Parsons and Charlesworth’s kits call attention to all those existential dimensions that can’t, or perhaps shouldn’t, be “kitted out.”

“Survival” writ large is a rather ambitious goal for a humble kit. But as anthropologist Peter Redfield explains, kits have long accompanied soldiers in battle and various mobile healers as they’ve attempted to ensure patients’ survival through medical means. He explains how Médecins Sans Frontières, or Doctors without Borders, has created kits to administer first aid at global scale. Designed for rapid delivery in emergencies and outbreaks via a sophisticated logistical system, these kits relieve doctors of the burden of locally procuring essential materials. What’s more, Redfield suggests, the kit functions as a form of “materialized memory”: “For an organization built around both crisis settings and a constantly shifting workforce of volunteers and temporary employees, such continuity would prove especially valuable.”[11] Kathryn Shroyer describes how we can “cognitively offload information into the environment through the organization of tools”; kits are a mechanism for distributed cognition.[12]

“Governing the [kit’s] overall design principles,” Redfield says, “are principles of quality, efficiency, and simplicity of maintenance.” In deployment, this results in a flattening of local differences. “The kit system is the exact opposite of local knowledge.” The kit “represents a mobile, transitional variety of limited intervention, modifying and partially reconstructing a local environment around specific artifacts and a set script.”[13] And while it reorganizes the local environment, it also “collect[s] and distill[s] local clinical knowledge into a portable map of frontline medicine”; it aggregates insight gathered in each deployment, and applies it at the next outbreak, thus “standardiz[ing] disaster through responding to it worldwide.”

Yet Redfield is careful to note that, while the kit’s development and distribution might require “factory-like processes of centralized control,” that standardization is meant to serve humanitarian ends – not to secure a profit. Techniques drawn from military logistics and commercial supply chains are here operationalized for rapid response to human suffering; the kit merely “solves the problem of missing infrastructure.”[14] Nevertheless, the complexity of that suffering also reveals the limitations of standardization. Redfield observes that, when targeting chronic diseases like HIV/AIDS, sustained conditions of psychological trauma, and other slower violences, the kit falters. A box full of surgical gloves and staplers isn’t going to thwart a persistent plague. In the face of sustained suffering, a kit is no substitute for robust, enduring, local, on-the-ground resources and expertise.

Much the same can be said of other humanitarian kits like the IKEA refugee shelter, which might serve as a valuable temporary solution to an immediate problem – but it does nothing to address the larger systemic geopolitical, economic, and climatic issues necessitating migration and causing housing precarity.[15] What about a kit that’s intended for more modest regional or local application, like community-led recovery in urban neighborhoods? In 2020, the Urban Design Forum and the Van Alen Institute teamed up and partnered with community organizations in several neighborhoods throughout New York City to create the Neighborhoods Now Toolkit, a set of designs, guidelines, and strategies to “aid safe reopening and recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic”; components include plans for on-street dining, creating open-air theaters, activating vacant lots, designing mobile barricades, and assembling civic space from a kit of parts.[16] While post-pandemic recovery does require engagement with existential questions not unlike those the preppers ask themselves – fundamental questions about shelter and public health and the provision of basic services and social infrastructures – these tools promote engagement rather than retreat. They function as vital stopgap measures, as means to patch back together a civic realm and remind us of the critical importance of safety and sociality and public space.

Kits are a mechanism for distributed cognition

Meanwhile, the People’s Kitchen Collective, an Oakland, CA-based, food-centered political education project, draws inspiration from Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, in which the protagonist, Lauren Olamina, facing the loss of her family and community, escapes with a bespoke bug-out bag made of pillowcases and clothesline. Into that makeshift kit she stuffs a canteen, a plastic bottle, matches, a change of clothes, shoes, a comb, soap, toothbrush and toothpaste, tampons, toilet paper, bandages, pins, needles and thread, alcohol, aspirin, a couple spoons and forks, a can opener, her pocket knife, packets of acorn flour, dried fruit and nuts, dried milk, her survival notes, plastic storage bags, plantable seeds, her journal, and her Earthseed notebook, where she outlines a new belief system rooted in change and adaptation.[17] That change requires engagement rather than survivalist isolation. The Collective Kitchen is in the process of manifesting Earthseed as “resource kits” that allow for the flourishing of a “nationwide meal series rooted in Butler’s theory of change, and the legacy of the survival programs of the Black Panther Party,” which included services offering free food, free dental care, free optometry, free clothing, free legal aid, free busing to prisons, free escorts for senior citizens, and a host of other resources.[18] For the Kitchen Collective, kits can help to standardize their distributed events in order to cultivate a sense of shared ritual. Having common protocols and a common governing doctrine – whether embodied in the form of a sacred text, a set of founding documents, or, here, a kit – can further promote nationwide solidarity, as was critical to the distributed chapters of the Black Panthers.

TOOLKITTING AS A STRUCTURE OF RELATION

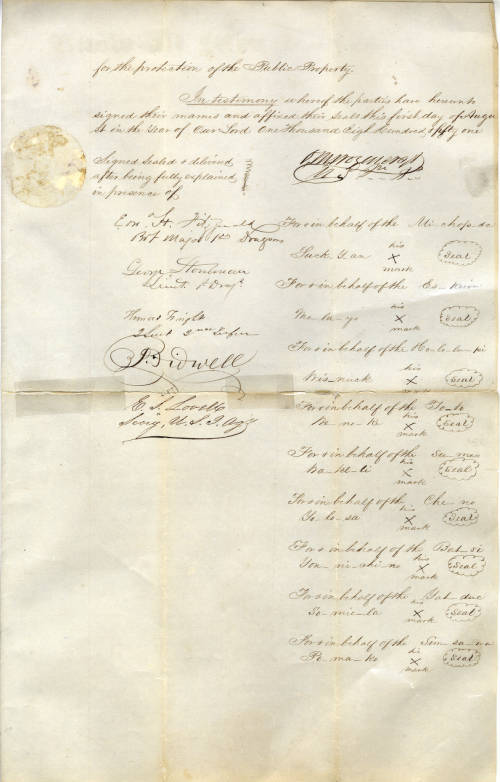

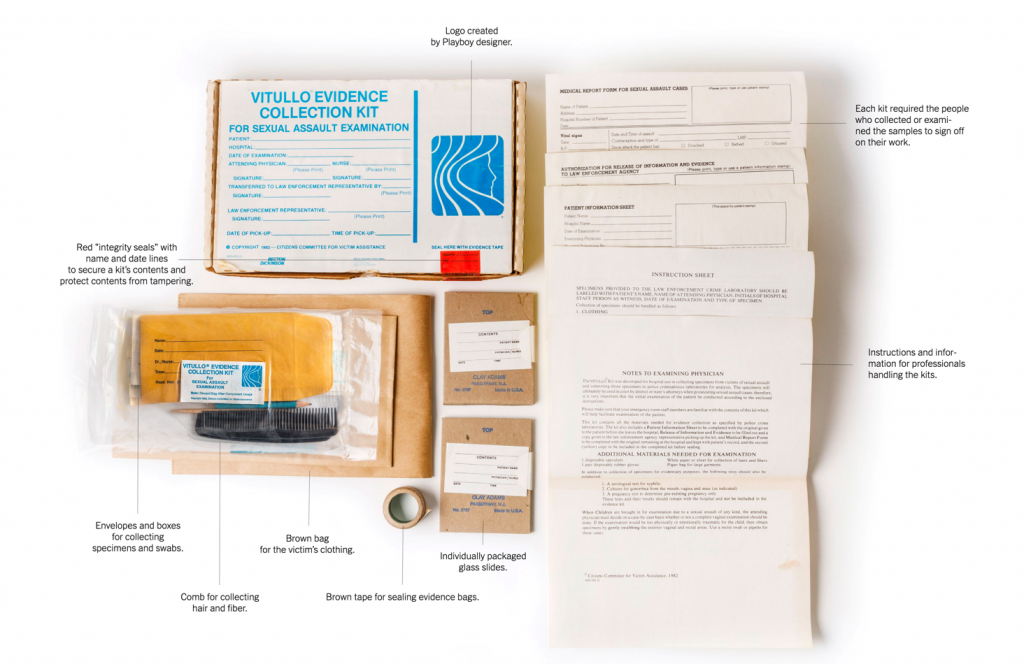

Kits are instrumental not only in the deployment of resources or provision of services. They’re not only memory devices, governing apparatae, and standardizing formats for experts or officials distributing their expertise and skills to others; kits also serve as tools of engagement, as methods of inclusion, for broader communities. In the 1970s, anti-rape activist Martha “Marty” Goddard took on the standard forensic methods deployed within the Chicago police department, which were based on the presumption that charges of assault were a “feminine delusion,” and that male police officers would serve as the voice of the purported victim. Goddard’s contribution: a kit composed of nail clippers, a comb for collecting hair and fiber, a bag for the victim’s clothing, a card offering her information about support services, test tubes, slides and packaging materials to protect the specimens, sealing tape, a pencil for labeling the slides, and forms for doctors and police officers. Goddard’s rape kit was a cardboard box full of disruptive contradictions: supported by a grant from the Playboy Foundation, branded blue and white by Playboy’s graphic designers, and assembled by a team of senior citizen volunteers at Playboy’s offices, the kit overturned conventions of practice and systems of authority. As Pagan Kennedy describes in a powerful and poignant piece in the New York Times, Goddard’s low-tech technology “blasted through the assumptions of the day: that nurses were too stupid to collect forensic evidence; that women who ‘cried rape’ were usually lying; and that evidence didn’t really matter when it came to rape, because rape was impossible to prove.”[19] The kit systematized evidence collection and produced a paper trail, which ultimately proved persuasive in the courtroom. The kit was both a scientific tool and a “theatrical prop,” Kennedy notes; it had such charisma, “the kit itself became a character in the trials.” Yet Goddard patented her invention under the name of Sergeant Louis Vitullo, the head of the Chicago Police Department’s microscope unit and her domineering collaborator, because, Kennedy argues, “the kit never would have had traction if a woman with no scientific credentials had been known as its sole inventor.” Men are the ones who make technology. Thus, while Goddard’s kit validated victims and nurses as authorities, Goddard herself wasn’t, for quite some time, included in the kit’s official history.

Kits also serve as tools of engagement, as methods of inclusion, for broader communities

We can observe similar contradictions in the case of the participatory development kit, a briefcase containing activity cards, pictures, charts, game pieces, puppets, and a guidebook – many of the same materials we’d find in an intelligence kit. Yet rather than evaluating subjects’ intellectual capacity, the participatory development kit was built on the assumption that all people are intelligent and entitled to contribute their ideas and opinions in shaping development projects in their own towns and cities. Created in 1994 by Lyra Srinivasan and Deepa Narayan, who worked at the United Nations Development Program and the World Bank, the kit built on a few decades’ worth of accumulating interest in participation: participatory development, participatory action research, participatory poverty assessments, participatory design, and so forth. It drew, too, on Paolo Freire’s ideas of critical consciousness, which can be achieved through the use of imagery and games and the validation of common folks’ perceptions.

As anthropologist Christopher Kelty observes, the participatory development kit embodies an enthusiasm for inclusivity, respect, and curiosity; its contents are “designed to draw people into discussing problems and situations that immediately affect them, to elicit stories and images of the future they would prefer to have, and to debate the solutions to the problems they experience.”[20] One means of addressing these questions is through comparing before and after scenarios: “pictures of an unsanitary, impoverished, violent” now, contrasted with renderings of a “cleaner, wealthier, more humane” later. Despite the obvious “enthusiasm” for inclusivity Kelty sees in the kit, we might wonder how the design of its various methodological tools might direct facilitators’ and participants’ curiosity – how the kit leads users toward particular conclusions (about the inevitability of colonial development), or how it “boxes out” particular modes of engagement or possibilities of resistance. As design scholar Ahmed Ansari suggests, the curiosity and enthusiasm infusing the kit serve a rhetorical function: “the toolkit is … not just simply trying to empower stakeholders, but to actively convince them of its own power as a means of giving them agency and control over their situations” – often via technosolutionist means.[21]

As with Redfield’s humanitarian kit, the participatory development toolkit is a “device for decontextualizing,” “scaling up,” and standardizing insight gathered on the ground in particular places. After all, the kit has a handle; it’s made to “travel,” Kelty says. (There’s more than just a formal resonance here with the old traveling salesman’s kit, stuffed with lightbulbs and vacuum nozzles and encyclopedias; the UNDP and World Bank are selling their wares in a suitcase, too.) Yet while the kit and its component tools themselves are uniform, they’re meant to lend themselves to adaptive deployment by a skilled facilitator. The kit says so explicitly: users encounter multiple caveats to contextualize and modify, to cede control to local participants. This kit, again like its humanitarian counterpart, aims to mediate between the universal and the locally specific “by taking what works at a local level, attempting to quasi-formalize it, and inserting it into a briefcase so that it can be carried to the next site to repeat its context-specific success.”

Such “franchising” raises suspicion – perhaps even more so than with the humanitarian kit because the medical treatment of bodies does require some standardized knowledge of how bodies work, whereas local populations’ diagnoses of local problems are highly contextual. As political ecologist Francis Cleaver proposes, “participation” in development “has been translated into a managerial exercise based on ‘toolboxes’ of procedures and techniques.”[22] What’s more, when those toolboxes are branded with the World Bank and UNDP insignias, participation seems “more or less bureaucratic” and official, institutionally standardized and underwritten by global capital and legacies of colonialism.[23] These very forces are precisely what the Social Design Toolkit prepares local communities to defend themselves against. Designer María del Carmen Lamadrid begins the guide by defining “social design,” hegemony, and neoliberalism, then explains how the toolkit’s cultural probes, activities, reading selections on postcolonial theory, and references to resistant social movements can “give community leaders tools to avoid being victims of social design,” which often “create entrepreneurial opportunities for [Western NGOs and commercial firms] instead of resolving the [local] problem.”[24] Hers is a toolkit to combat the hegemony of the developer’s toolkit.

The participatory development kit was built on the assumption that all people are intelligent and entitled to contribute their ideas and opinions in shaping development projects

Yet the toolkit’s local impact is often multifarious. We might be more attuned to considering these differences if we recall that social psychologists think of toolkits differently: they use the term to refer to the resources necessary to construct “strategies of action” to, say, achieve a goal or solve a problem; those strategies are shaped by groups and societies in which one is embedded, and the situational contexts in which one finds oneself.[25]

Ansari asks: “What does happen when the universal toolkit with its universally applicable forms of knowledge is translated and exported to other countries? Whose hands does it end up in? How is it used? How does it transform the creative economy? How does it transform the nature of design practice and pedagogy? How does it transform the social and political dimensions of local practice?”[26] In Pakistan in the early aughts, Ansari told me, design wasn’t regarded as a research-driven discipline, but the kits created by various NGO’s and prominent design consultancy IDEO exposed local designers to the idea of research in design, and were used to train Pakistani practitioners.[27]

Yet “training” isn’t the only mode of learning that toolkits make possible; rather than prescribing a delimited set of professional practices, they can also open up opportunities for less scripted exploration and experimentation. Kits used in pedagogy and collaborative learning can also create a different politics of inclusion – who gets to make and learn, and how? – than we observed in the criminological, legal, and development realms. We turn in our next section to these teaching and learning toolkits.

TEACHING WITH TOOLKITS

Goddard’s lack of recognition in the rape kit’s legacy, and the potential tokenization of locals through the “toolkitting” of their inclusion in development projects that are all but inevitable, doesn’t mean that toolkits are inherently inimical to respectful, meaningful engagement. As Iris van der Tuin explains, toolkits are particularly useful in interdisciplinary research collaboration; they help to construct a shared language and process – they “externalize and formalize a set of steps,” as we saw with the Doctors Without Borders kits – and thereby cultivate “just enough commonality” to create “conceptual, epistemic, and empirical common ground.”[28] Kits are what Susan Leigh Star and James Griesemer call “boundary objects”: they’re “both plastic enough to adapt to local needs and constraints of the several parties employing them, yet robust enough to maintain a common identity across sites.”[29] They’re mediators, translators. In her study of the use of toolkits in collaborative service-learning courses, where design students are partnering with external partners, Susan Melsop notes how toolkits give the non-designers material prompts to empower them to express themselves. They helped diverse participants create common goals and build trust, and they “provided a means toward communal participatory action.”[30] The kits’ very materiality represents the potential for embodied learning.

Community Tech New York, an organization committed to digital justice and to building community power through community-owned internet infrastructure, offers “portable network kits,” “a wireless network in a suitcase that helps people [learn] how to build their own mini-internet – and with it, how the internet works and might be owned and governed more equitably.”[31] The kits serve both as a teaching tool and an “emergency standalone wireless network.” Unlike the humanitarian and development kits, the network kits down-scale an intimidatingly, inaccessibly complex infrastructure to make it intelligible and manipulable for common folks. The Community Tech team specifies that the kits “are not a product”; they’re used for “training community members in network development and deployment, giving them practical hands-on experience that can serve as a springboard for building their own networks.” And building their own networks, as CTNY Director Greta Byrum writes, gives communities an opportunity to choose which values they want to instantiate in the infrastructure that binds them together.[32] All that from a box of cables!

“CheapJack,” one of the leaders of the #CriticalKits project, acknowledges that kits’ convenience, attractiveness, mobility, and reproducibility make them “capable of distributing power, knowledge and agency,” the goal of many of the cases we’ve explored here. Yet “by abstracting and simplifying complicated components or concepts into kits for mobility and ease of use,” he argues, they remove opportunities for deeper nuanced experiences of understanding and learning… [They] can make us feel like we are in control, literate and resilient when we are not.”[33] This is certainly true in the case of the prepper kit and the development kit, for example. We might also extend the critique to science kits and to model kits, which cultivate the delusion that one is manipulating the forces of the universe, or creating a hermetically sealed world in miniature.

Even food kits – cake mixes, TV dinners, and contemporary meal kits like Blue Apron – could be charged with “alienating” home cooks from food production. Consider the case of Oscar Mayer’s Lunchables.The cold-cut-based meal kits were originally intended for adults, as a lunch “solution” for working parents, but they discovered that kids enjoyed the “ritual” of opening the box and peeling off the top, and the craft of “assembling their meals”: in other words, stacking flat processed foodstuffs (perhaps preparing them for later assembling flat-packed pressed plywood pieces into IKEA furniture).[34] The plastic tray was inspired by TV dinners, which were themselves spawned in the 50s; and the novel packaging was an attempt to reposition bologna, which began to wane in popularity in the mid 1980s. Focus groups revealed that working moms felt guilty about not providing their kids with a proper lunch, so Oscar Mayer stuffed the tray into a bright yellow box, which was meant to evoke wrapping paper; mom could thus send the kids off to school with a little gift. After launching nationally with its staple meat-and-cheese trays in 1989, the company later added pizza meals, organic options, and some “Around the World’ international variations. They tried healthier versions, but they didn’t sell, and the fruit sides didn’t ship or store well, so Oscar Mayer eventually returned to its “indulgent positioning,” a food industry analyst told The Atlantic. These food product kits – of which I enjoyed my fair share in the early 1990s – are thus products of manufacturing and marketing and commodity fetishism and capitalist productivity and parental guilt. If they distribute any power and agency, it’s in allowing kids to stack their own sodium bombs. If they cultivate any knowledge about technology, it’s in reminding us that processed food is a technology. But they also serve as convenient tools for exhausted working- and middle-class parents to feed and entertain their children when there’s simply no time for a bespoke bagged lunch or a family meal.

And boxed bologna isn’t necessarily cheesy (pun intended). The food kit also has the potential to offer an aesthetic education. Consider, now, the Japanese lunchbox. Kenji Ekuan describes its pleasures and profundities: “The greatest pleasure of the lunchbox comes when you take off the lid and sit for a moment gazing at the various delights inside…. There is marvelous discipline here – a power of form that amply allows for plurality.”[35] We can’t quite say the same of machine-pressed ham rounds and cheese squares, but the bento box, Ekuan rhapsodizes, embodies beauty of form, functional multiplicity, unification in diversity, ultimate adaptability, and generosity – and it’s an object lesson in waste-avoidance. It demonstrates how equipment – the box with its multiple partitions – can “excite creativity.” These kits invite aesthetic appreciation of their individual components’ complexity, of the assemblage’s harmony, of their creators’ skill. Rather than “removing opportunities for deeper nuanced… understanding and learning,” as CheapJack proposes, the boxes provide a scaffolding for it. They cultivate discipline, literacy, and resilience – the very qualities CheapJack suggests that they might preclude.

The bento box embodies beauty of form, functional multiplicity, unification in diversity, ultimate adaptability, and generosity – and it’s an object lesson in waste-avoidance

Despite the pejorative connotations of being “boxed in,” boxes can be portals to a worldly, sensory education. In the early 19th century clergyman and professor Charles Mayo traveled to Switzerland to study with education reformer Johann Pestalozzi, who advocated for children’s embodied engagement with their material environments. He returned to London and established a school outside of London, and his sister, Elizabeth, published a book to support the school’s curriculum: Lessons on Objects offered 100 lessons on 100 objects. As Ann-Sophie Lehmann explains, the curriculum was built on the assumption that “the qualities of materials should first be experienced before they are defined with specific terms: only after a child has bent a piece of whalebone back and forth should it become acquainted with the term ‘elastic,’ because only then can the new word really be grasped and remembered.”[36] An advertisement at the back of the book notes that “cabinets, containing the substances referred to in these lessons,” can be purchased at various shops.[37] Those mahogany boxes, Lehmann writes, “are extraordinarily beautiful in the way they hold the material universe, stacked neatly in four trays.” Unlike wunderkammern, which display the rare and curious, these boxes catalogue the quotidian. “In the lower left corner, we encounter the quill, the pencil and the ladybug, which together serve to embody the profound contrast between nature and artifice, life and death. Only the flower is missing. We can assume that it would have been plucked directly from nature for this purpose, just like milk and an egg are present in the book but not in the box.”[38] And another: the objects in this box “are heavily worn. The wear and tear evokes the performative space, in which the book and the objects must have met during teaching: stuff was used, broken, and lost, and teachers needed to replace and thereby expand the repertoire of the Mayos.”[39] These wooden boxes contained pieces of a world that students were encouraged to scrutinize and fondle and sniff, with the hope that such engagement would prompt a similar sensory engagement with the broader world beyond the kit, the classroom, and the school building that contained it. [40]

That world’s materiality became more complicated as we recognized its suffusion with electromagnetic waves and digital bits. In the 1960s Bell Labs created science kits, which they offered to primary and secondary school teachers, to teach students about electronics and computation.[41] The crystallography kit contained a rotary crystallizer tank; the parts necessary for students to build a polarizing microscope; samples of mica, calcite, and other crystalline materials; a book of experiments; and a reference book. Other kits came with film strips and wall charts. Berkeley Enterprises, an early computing firm, sold its Brainiac Kit, which offered an “introduction to the design of arithmetical, logical, reasoning, computing, puzzle-solving, and game-playing circuits – for boys (just boys!), students, schools, colleges, designers.”[42]

In more recent years, the Center for Urban Pedagogy has created kits – often in collaboration with secondary school students – that serve to engage the general public in abstract, bureaucratic (and, frankly, not always terribly sexy) topics, like affordable housing, zoning, and the Uniform Land Use Review Procedures. Their kits often contain models and games and films, which make material and experiential these seemingly stodgy subjects.[43] In my own Urban Intelligence studio, which I taught in 2017 and 18, I invited students to create “urban IQ test kits” for the “smart city,” which forced them to find empirical evidence of all the ways a city is smart; our primary goal was to demonstrate how many forms of urban intelligence – local and indigenous knowledges, lessons ingrained in the landscape itself – simply don’t lend themselves to standardization, measurement, and “kittification.”

TOOLKITTING AS DESIGN

Yet the design world has often promulgated, through charismatically designed toolkits, a sense of design itself as a standardized, systematized, scripted process. Those kits often take the form of card decks. Consider MethodKit, which offers a veritable library of decks on pretty much any conceivable topic: from workshop planning and personal development to public health and gender equity.[44] There’s also the Ethical Explorer Pack, which includes resources to help designers and digital product developers consider “risk zones,” surveillance, algorithmic bias, and other ethical concerns when developing new “responsible tech.”[45] The Imaginaries Lab offers its Metaphors toolkit, a set of cards that encourage us to think about how metaphors shape our understanding of the world and our capacity to imagine how it could be otherwise.[46]

“Design thinking” instigator IDEO embodies its signature approach in its Design Kit, which offers resources on dozens of uplifting “mindsets” – “learn from failure,” “creative confidence,” “empathy,” “embrace ambiguity” (all of which feel like they’re begging for exclamation points!) – and methods, from “expert interview” to “peers observing peers” to “gut check” to “rapid prototyping.”[47] Those methods have been transformed into a card deck, too – as have hundreds, if not thousands, of other branded design methods. And those decks increasingly take the form of tarot decks, which might make us ask what forms of knowledge (or belief) and agency are conjured up through the design process. What might be the epistemological fallout of parceling out deliberative processes into a deck of cards – of flattening a “kit” into a “deck”? How does the formalism of method shape the way we design the world?

Perhaps our toolkits can offer new ethical and pedagogical frames, reshaping the contexts for tool use – and informing the worlds we build with them

There’s even a ToolboxToolbox, which is, as its name implies, a kit of kits attesting to the proliferation of toolboxes to solve problems and address challenges ranging from remote work to venture design to racism and decolonization.[48] Again, our previous discussion should prompt us to wonder: can all such “problems” be solved with a kit-of-parts methodology, by shuffling a deck?

We can trace one of the designerly toolkit’s, or card deck’s, genealogical lines back to the rise of Design Methods in the 1970s, which was rooted partly in a desire to systematize and externalize design’s mystified, “black boxed” processes – to make it seem more like science than tarot. As Ansari describes in his discussion of the Design Methods and Design Thinking movements, several central Methods advocates eventually distanced themselves from the movement because they observed mounting dogmatism and rigid adherence to formalized rules and procedures. “Design thinking,” with its focus on “pattern sensing, reflexivity, intuitively and experientially informed judgment,” emerged as a corrective.[49] Ansari suggests that we see these two approaches – systematic rules and intuition – merging in the toolkit and card deck. Given its capacity for materializing memory and method, as we’ve seen in the previous examples, the kit was an ideal means to transform design’s black box into a literal box, and then to stuff that box with a host of prompts and probes that promote reflection and (ostensibly) value intuition and sensory experience.[50]

A few years ago I wrote about what I perceived as a growing interest among citizen scientists and designers in the aesthetics of measurement – a fascination that manifested in the creation of lots of stylized kits.[51] Researchers seemed to be fascinated then – and still are! – by the sensory, affective, subjective dimensions of measuring things, and, to feed their passion, they designed a host of measurement tools as objets d’art: lovely little bento boxes of tools, fanciful surveying equipment, deliciously weird Tom Sachs-ish visioning machines. Speaking of Sachs: we can certainly see the influence of the artist’s own modus operandi, knolling, or the ordered arrangement of objects, in many of these projects. There are also clear ties to Duchamp’s La Boîte-en-valise, Fluxus Fluxkits, and Aspen’s multi-format publications-in-a-kit.

I wondered what has made measurement and data collection — often with analog tools — so cool, so worth aestheticizing, in this age of sentient technologies and planetary computation. Perhaps it’s partly because, in contrast with the machines automatically harvesting mountains of data, these toolkits allow for a slower, more intentional, reflective, site-specific, embodied means of engaging with research sites and subjects. They allow researchers to design their methods and measurement devices, including some that, drawing on the principles of Maker culture, deploy the same computational methods used in surveillance and data mining, but use them, as does the Social Design Toolkit, to critique those very computational methods and suggest other, more responsible, less exploitative, more poetic uses.[52]

Perhaps these assemblages of tools, these methodological bento boxes, can be like the Japanese lunchbox in that they invite us to reflect upon the delights inside – the forms and affordances of each tool, and the discipline each requires. Seeing those tools in relation to each other, we can inquire about the multiple adaptive functions they might serve, how they complement one another, how they can cultivate generosity. As Audre Lorde has reminded us, tools forged through a particular politics – whether patriarchy or racism or neoliberal technofetishism – might not be able to undermine that political regime. Yet perhaps our toolkits can offer new ethical and pedagogical frames, reshaping the contexts for tool use – and informing the worlds we build with them.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: Thanks to Tega Brain and Ahmed Ansari, who invited me to develop this project as a keynote for the North American PhD by Design conference; you can find a video of the talk, featuring dozens of images of kits, here. Thanks, too, to the conference attendees for their valuable feedback. I’m also grateful to Edward Morris, Susannah Sayler, and Tim Furstnau for their helpful edits.

- Oxford English Dictionary. ↑

- These various test kits – the “form boards” used by Howard Andrew Knox at Ellis Island, the Stanford-Binet Scales package, the Merrill-Palmer Scale of Mental Tests, the Lowenfeld Mosaic Plates, and the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale kit, to name just a few – are a means of materializing a methodology and an epistemology, one that reifies and objectifies the idea of intelligence as something empirically measurable. See Sasha Bergstrom-Katz’s “On the Subject of Tests” project: http://www.sashabk.com/projects. ↑

- “The Birth of the First Aid Kit,” Johnson & Johnson: Our Story: https://ourstory.jnj.com/birth-first-aid-kit. ↑

- Steven M. LaBarre, “The American Housewife Goes to War: Sewing Kits that Accompanied the American Soldier to the Front, 1776-1976,” Masters Thesis, University of Nebraska at Kearney (2020): https://search.proquest.com/docview/2444898664?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true. ↑

- Stacey Dee Woods, “The Best Items to Stock for Any Emergency, According to Survivalists,” THe Strategist (November 20, 2020); https://nymag.com/strategist/article/best-emergency-kit-items.html; “Family Preparedness Packages,” Stealth Angels Survival: https://www.stealthangelsurvival.com/collections/emergency-kits; John Ramey, “Emergency Kit / Bug Out Bag List,” The Prepared (December 21, 2019): https://theprepared.com/bug-out-bags/guides/bug-out-bag-list/. I am grateful to the participant in the PhD by Design conference, where I shared a draft of this article, who reminded me that disabled people often engage in “prepper”-like behavior in order to avoid the potential loss of access to necessary supplies and services during a crisis. ↑

- “The Du Boisian Visualization Toolkit,” Dignity & Debt: https://www.dignityanddebt.org/projects/du-boisian-resources/; Mindaugas Gapševičius, “My Collaboration with Bacteria for Paper Production”: http://triple-double-u.com/my-collaboration-with-bacteria-for-paper-production/; Libraries Without Borders, Ideas Box: https://www.librarieswithoutborders.org/ideasbox/. ↑

- Kezia Barker, “How to Survive the End of the Future: Preppers, Pathology, and the Everyday Crisis of Insecurity,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 45:2 (2020): https://rgs-ibg.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/tran.12362. See also Anna Bounds, Bracing for the Apocalypse: An Ethnographic Study of New York’s ‘Prepper’ Subculture (Routledge, 2020). ↑

- Quoted in Barker. ↑

- Bradley Garrett, “Doomsday Preppers and the Architecture of Dread,” Geoforum (online April 2020): https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016718520300804?via%3Dihub. ↑

- “New Survivalism: The Rewilder (Future),” Parsons & Charlesworth: https://www.parsonscharlesworth.com/new-survivalism-the-rewilder/. ↑

- Redfield: 157, 158. ↑

- Kathryn E. Shroyer, “Distributed Cognition as a Theoretical Lens for the Design of Makerspace Tool Kits,” ISAM (2018): 2. ↑

- Redfield: 161. ↑

- Redfield: 165. ↑

- See Tom Scott-Smith, “Beyond the Boxes,” American Ethnologist 46:4 (November 2019): 509-21: https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/amet.12833. ↑

- Urban Design Forum and Van Alen Institute, Neighborhoods Now Toolkit: https://neighborhoodsnow.nyc/. ↑

- Elizabeth Losh writes, “As she acquires items in her inventory, [Lauren’s] communal vision redistributes the survival kit’s materials and redesigns its economic function as property…. By grounding her refugees’ stories in their access to particulars – nuts, matches, knives, sleep sacks, lip balm – Butler lets us understand both the tenacity and the tenuousness of subject-object relations located outside of the circuit of conventional consumer commodity fetishism.” ↑

- People’s Collective Kitchen, “Earthseed,” Creative Capital: https://creative-capital.org/projects/earthseed/. ↑

- Pagan Kennedy, “The Rape Kit’s Secret History,” New York Times (June 17, 2020): https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/06/17/opinion/rape-kit-history.html; see also Anisha Chadha, “Chains of Custody,” American Museum of Natural History (2017): https://www.amnh.org/explore/margaret-mead-film-festival/archives/2017/films/chains-of-custody%20. ↑

- Christopher M. Kelty, “The Participatory Development Toolkit,” limn 9 (2017): https://limn.it/articles/the-participatory-development-toolkit/. See also Christopher M. Kelty, “Participation, Developed,” in The Participant: A Century of Participation in Four Stories (University of Chicago Press, 2019): 183-248. ↑

- Ahmed Ansari, “Global Methods, Local Designs” in Elizabeth Resnick, ed., The Social Design Reader (Bloomsbury, 2019); available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329375448_Global_Methods_Local_Designs, p. 5. ↑

- Frances Cleaver, “Paradoxes of Participation: Questioning Participatory Approaches to Development,” Journal of International Development 11 (1999): 608. ↑

- Kelty, “The Participatory Development Toolkit.” ↑

- Change for Social Design, Social Design Toolkit (2013): https://issuu.com/mlamadrid/docs/toolkit, p. 1; María del Carmen Lamadrid, “Change for Social Design: The Social Design Toolkit,” Malamadrid (February 16, 2019): http://cargocollective.com/mlamadrid/following/all/mlamadrid/Change-for-Social-Design-The-Social-Design-Toolkit. Thanks to Anne Burdick and Daniel Rosner for the reference. ↑

- Ann Swidler, “Culture in Action: Symbols and Strategies,” American Sociological Review 51:2 (1986): 273-86. See also Jessica McCrory Calarco, “Th Inconsistent Curriculum: Cultural Tool Kits and Student Interpretations of Ambiguous Expectations,” Social Psychology Quarterly 77:2 (2014): 185-209. ↑

- Ahmed Ansari, “Global Methods, Local Designs” in Elizabeth Resnick, ed., The Social Design Reader (Bloomsbury, 2019); available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329375448_Global_Methods_Local_Designs, p. 6. ↑

- Ahmed Ansari, personal communication, April 10, 2021. On March 8, 2021, UN-Habitat and the Global Utmaning think tank launched “Her City Toolbox,” a platform for increasing girls’ participation in urban development around the world. How might such targeted outreach shape urban design? See “Launching Her City Toolbox,” UN-Habitat: https://unhabitat.org/events/launching-her-city-toolbox. ↑

- Iris van der Tuin, “Creative Urban Methods: Toolkitting as Method” (forthcoming) https://www.kwalon.nl/blog/. ↑

- Susan Leigh Star and James Griesemer, “Institutional Ecology, ‘Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology,” Studies of Social Science 19:3 (1989): 393. ↑

- Susan Melsop, “Community Design Matters: A New Model of Learning,” Design Principles and Practices (January 2010): 8. ↑

- Community Tech New York, “Portable Network Kits”: https://www.communitytechny.org/portable-network-kits; Community Tech New York, PNK Video: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Hk6jPBguB3dyLYB8waguh_KX0leW8LRq/view.See also “Neighborhood Network Construction Kit,” Community Technology Field Guide: https://communitytechnology.github.io/docs/cck/index.html; and Rory Solomon, “Unpacking a Mesh Install Kit: An Object Lesson in Community Network Maintenance,” Maintainers III, Washington, D.C., October 8, 2019, https://miii.sched.com/list/descriptions/type/Information. ↑

- See Greta Byrum, “Building the People’s Internet,” Urban Omnibus (October 2, 2019): https://urbanomnibus.net/2019/10/building-the-peoples-internet/. See also the various digital literacy and digital justice kits — which are more like “resource guides” — from organizations like the Data Justice Lab and Tactical Tech. ↑

- “Critical Kit Resilience,” CheapJack (July 5, 2018): https://cheapjack.github.io/2018/07/05/critical-kit-resilience. See also Critical Kits and How We Use Them (RE-DOCK / Creative Commons, 2017). ↑

- Joe Pinsker, “The 30-Year Reign of Lunchables,” The Atlantic (November 17, 2018): https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2018/11/lunchables-30-years-invented-history/576025/. See also “Lunchables Commercial 1989,” YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hlQ-Fhrha7g. ↑

- Kenji Ekuan, The Aesthetics of the Japanese Lunchbox (MIT Press, 2000): 1. ↑

- Ann-Sophie Lehmann, “Cube of Wood: Material Literacy for Art History” (Groningen: Rijksuniversiteit, 2016): 10. See also Ann-Sophie Lehmann, “Material Literacy,” Bauhaus Zeitschrift 9 (2007): 20-7; and Haidy Geismar, “Object Lessons: The Story of Material Education in Eight Chapters,” Material World (August 31, 2016). ↑

- Lehmann: 10-11. ↑

- Lehmann: 12. ↑

- Lehmann: 13. ↑

- Jentery Sayers has updated the Mayo object box with his Kits for Cultural History: Hyperrhiz 13 (Fall 2015): http://hyperrhiz.io/hyperrhiz13/workshops-kits/early-wearables.html. ↑

- “Bell System has New Teaching Aids for High School, Elementary School,” The Journal of the Telephone Industry (February 27, 1965); “Bell Labs Science Experiment Kits,” The Porticus Centre: https://www.beatriceco.com/bti/porticus/bell/belllabskits.html. ↑

- “Brainiac: A Better Electric Brain Construction Kit,” Advertisement, Computers and Automation 8:1 (January 1959): 21. ↑

- Center for Urban Pedagogy, “Envisioning Development”: http://welcometocup.org/Projects/EnvisioningDevelopment; “What is Affordable Housing?: http://welcometocup.org/Projects/EnvisioningDevelopment/WhatIsAffordableHousing; What Is ULURP?: http://welcometocup.org/Projects/EnvisioningDevelopment/WhatIsULURP; Zoning Toolkit Workshop: http://welcometocup.org/NewsAndEvents/ZoningToolkitWorkshopAtTheNewMuseum. See also the Public Library Exchange’s kits for learning in libraries: PLIX, Creative STEM Learning in Libraries: https://plix.media.mit.edu/activities/; *Paper Circuits: https://plix.media.mit.edu/activities/paper-circuits/; Urban Ecology: https://plix.media.mit.edu/activities/urban-ecology/; DataBasic: https://plix.media.mit.edu/activities/databasic/. ↑

- MethodKit: https://methodkit.com/. ↑

- Ethical Explorer: https://ethicalexplorer.org/. ↑

- Dan Lockton’s Imaginaries Lab Metaphors toolkit: http://imaginari.es/new-metaphors/ and http://newmetaphors.com/. ↑

- IDEO, DesignKit: https://www.designkit.org/. ↑

- ToolboxToolbox: https://www.toolboxtoolbox.com/. ↑

- Ansari: 3, 4. See also Nigel Cross, “Designerly Ways of Knowing,” Design Studies 3:4 (1982): 221-7; John Chris Jones, Design Methods: Seeds of Human Futures (Wiley, 1970); and ]Daniela K. Rosner, Critical Fabulations: Reworking the Methods and Margins of Design (MIT Press, 2018): 24-39. ↑

- Elizabeth B.-N. Sanders and Pieter Jan Stappers explain the distinctive processes and purposes of probes and kits: “Probes,” they say “originated in the design-led and expert-driven corner of the map whereas generative toolkits originated in the design-led and participatory corner of the map. The probes approach invites people to reflect on and express their experiences, feelings and attitudes in forms and formats that provide inspiration for designers.” Meanwhile, “generative toolkits describe a participatory design language that can be used by nondesigners (i.e. future users) in the front end of design so that they can imagine and express their own ideas about how they want to live, work and play in the future.” Toolkits, they propose, “follow a more deliberate and steered process of facilitation, participation, reflection, … making understandings explicit, discussing these, and bridging visions, ideas and concepts for the future,” as we saw with the participatory development kit. Elizabeth Sanders and Pieter Jan Stappers, Convivial Toolbox: Generative Research for the Front End of Design (BIS Publishers, 2012): 8. ↑

- Much of this section is adapted from Shannon Mattern, “Methodolatry and the Art of Measure,” Places Journal (November 2013): https://placesjournal.org/article/methodolatry-and-the-art-of-measure/. ↑

- CheapJack proposes that “critique itself can [come] in kit form.” #CriticalKits are self-aware; their creators know that kits often reflect “neoliberalism’s adoption of maker-culture,” as well as colonialism’s and corporatism’s attempts to globalize local techniques – and they thus aim to design into their very form a subversion of rationalist, functionalist, extractivist logics? (Critical Kits and How We Use Them (RE-DOCK / Creative Commons, 2017): 5). ↑