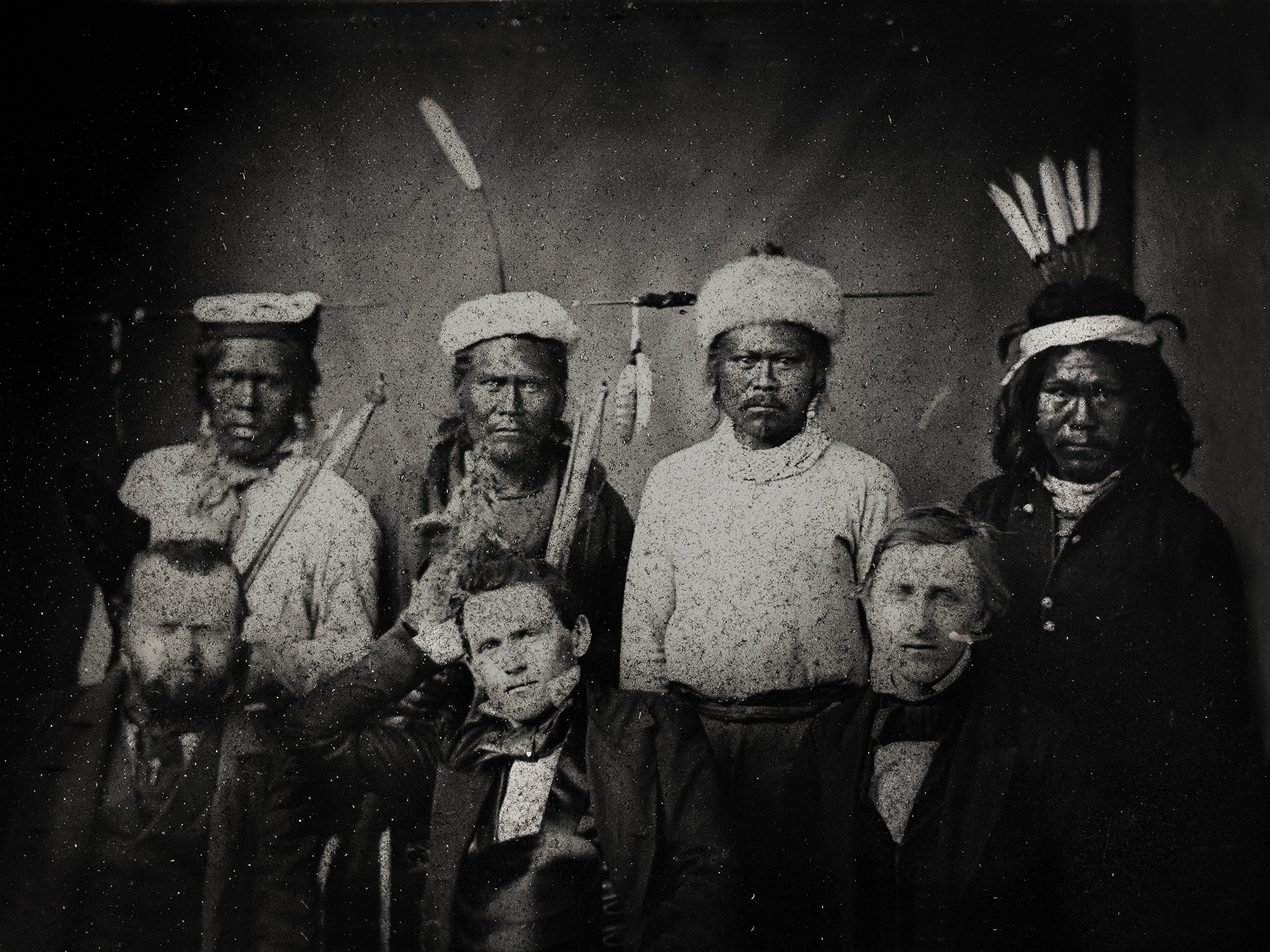

Before we say anything, we ask that you look closely at the above image.

Look at each person, one by one, then shift your focus back to the whole group. (This exercise unsettles us, perhaps because the meaning of the group in this image, appearing as part of the historical record, so thoroughly erases the individuals, the fullness of their lives).

Find the individuals again. Now, try to meet the gaze of those who look directly at “you”– you who uncannily become the photographer… or rather the camera. Yes, you, the spectator, are the camera. You are re-capturing the image, now, in this moment. You are re-seeing what another saw, but with a more uncertain intent. Forget about your intent, your intent is changing as you are looking and that is dizzying and takes you out of the image, into yourself. You can return to that later.

Right now be a machine, slow down, return to the gaze, first of the seated one in the center-front, who is signifying control and confidence with his posture– he is posing is he not? His gaze definitely stops at you– is intended for you, the camera. He is saying, “I am in charge. I got this.” He wants you to know this.

Now look at the one just behind him, the one with what appears to be a tall feather. What is he signifying exactly with his gaze? He seems somehow more still and vivid than the rest. His gaze does not stop at you, but seems to burn through the image, through you, reaching behind you. Towards what? But your own gaze is fixed. You can not look to the left or to the right and you certainly cannot look behind. What is he looking at, if not you? But, if you are looking inexorably towards the past and he is looking through you, towards something behind you, then is he not looking at the future– the future you cannot see but that he can? He betrays no emotion about what he sees. He is not posing.

There is a secret agreement between past generations and the present one.1

Like us, the philosopher Walter Benjamin lived in dark times. He was born in Germany in 1892 and fled in 1940. He was Jewish. He committed suicide on the French-Spanish border, fearing the next day he would be captured by Nazis. It is unclear if this specific, imminent fear was, in fact, justified. But his fear in general was without question its own sort of knowledge.

Benjamin knew what it means to be pursued by history–a knowledge, shifting between the conscious and unconscious, of being (pre)determined as a person by history, and also the more visceral feeling of being threatened bodily by that history. This knowledge, finding no possibility of absolute verification because internalized, can torment an individual as a state of paranoia, or be dismissed by others as “mere” emotion.2 It is perhaps most acute in those objectified by racism or subject to other ongoing impacts of colonialism. Increasingly, however, this sort of felt knowledge is becoming more broadly held, as those deeply conscious of the climate crisis yield to it3, and perhaps this can become a tool of understanding and of common cause.4 How? By becoming the ones “writing” history, instead of the ones subject to it.

Our use of the word history here– including our sense of what it means to “write” it and how such writing can be a redemptive act–comes from our reading of Benjamin. Benjamin thought of writing history as akin to remembrance. When we remember things from our own life, we have a purpose. We are reaching into our past and bringing it forward into the present, often because we need that memory in some way. It is not possible to distinguish whether that need is well-reasoned or “merely” emotional. Such a taxonomy has no place in our personal psychology. Further, it is irrelevant in those moments of remembrance whether the images we draw forth are “accurate” per se. What is vital is their relation to our present self, our need for them in ways of which we may not even be fully conscious. Benjamin regarded history as an analogous process of remembrance but for a collective rather than an individual purpose. “To articulate the past historically,” he wrote, “does not mean to recognize it ‘that way it really was.’…It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up in a moment of danger.”

However, unlike in personal remembrance, Benjamin believed there is a necessity in collective remembrance to understand the origin of that need. The images the historian grabs hold of from the past are the ones she needs now to protect against a threat. What threat? For Benjamin, in all epochs across time this threat takes a general form about which he was very explicit. It is: “the threat…of becoming tools of the ruling class.” Against such imminent domination, the historian of Benjamin’s ilk provides “nourishing fruit” and fans “the spark of hope” knowing that “even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins.” The reason the dead are not safe from this enemy is quite straightforward: they will be erased. The statue will be for Columbus and not for the Taino people who resisted the murder and slavery Columbus brought to them.

So, unlike personal remembrance, which is often involuntary and without definite purpose, the “writing” of history requires deliberation and choice. In the Benjaminian mode, however, this deliberation involves other techniques than writing and has a more democratic potential. The deliberation is not simply a choice about what “facts” to present and what “facts” to suppress. It is a matter of representing those facts in a way that conveys their urgency to the present moment. As the artist-historian Walid Raad writes (echoing Benjamin): “We are concerned with facts, but we do not view facts as self-evident objects that are already present in the world. One of the questions we find ourselves asking is, How do we approach facts not in their crude facticity but through the complicated meditations by which they acquire their immediacy.” 5

To be pursued by history in this sense does not mean simply to be haunted by events in the past. It means to be shaped, threatened, and hunted by the continuing impacts of those events, particularly as those events are mediated through the sanctioned stories we tell of the past and that through this process appear to define a sort of inevitability, something “natural.” Those who feel this threat, know it. Their feeling is knowledge. The various expressions of this felt-knowledge–organized protests, but also everyday acts of frustration; a dedicated attempt to describe a lived reality, but also an offhand comment– are thus not severed from the past but an integral part of a claim to its present immediacy. For Benjamin, the specific job of conveying this knowledge of lived experience in all its disparate mediations is the job of the committed historian.

This is not a theory of history. This is the conversion of history from oppressive science to tool.

To articulate the past historically does not mean to recognize it ‘that way it really was.’…It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up in a moment of danger. 6

Let us return to the image we started with and look at it again in this spirit of remembrance.

The white guy sitting in the center with the relaxed, confident posture was named Oliver M. Wozencraft. The federal government appointed Wozencraft to negotiate “treaties” with the indigenous people of California in 1851. These treaties were being pursued after a barbaric genocidal campaign, the true nature of which most Americans remain ignorant. This campaign was pursued explicitly in the name of seizing land for gold mining and colonization. The Governor of California at the time explicitly declared that “a war of extermination will continue to be waged…until the Indian race becomes extinct.”7 Both the state and federal governments supported the genocide, giving away land grants and providing high salaries to those who participated in raids against the Indigenous peoples. At the local level, towns and counties sometimes offered direct bounties on scalps, as much as five dollars a head (at a time when the average daily wage was about three dollars). As a result, the Indigenous population in California sank from 150,000 to 15,000 in two generations.8

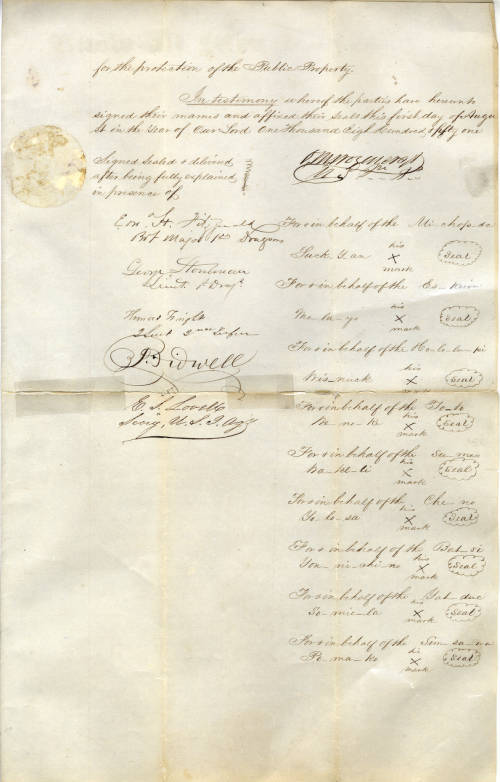

Wozencraft was then tasked with formalizing the displacement and primitive capital accumulation. He was accompanied in this task by the other two seated figures. This image was taken by an unknown photographer at the signing of one of these so-called treaties, this one with representatives of the Maidu people in August 1851. In the Eastman Kodak archives where we first came across this image, it is titled “Maidu Headmen and Treaty Commissioners.” The headmen are usually not identified by name when the image is reproduced; Wozencraft usually is. However, the treaty document produced that day gives the names of nine men representing nine bands of Maidu: Luck-y-an of the Mi-chop-da, Mo-la-yo of the Es-kuin, Wis-muck of the Ho-lo-lu-pi, We-no-ke of the To-to, Wa-tel-li of the Su-nus, Yo-lo-sa of the Che-no, Yon-ni-chi-no of the Bat-si, So-mie-la of the Yut-duc, and Po-ma-ko of the Sim-sa-wa.9 Their signatures are represented by an “X.” The four men in the image presumably came from among these nine bands.10

In Wozencraft, what sort of man did the United States of America empower to “negotiate” these “treaties?” The same man who two years earlier in 1849, as a delegate to the California Constitutional Convention, argued for a law outright barring all people of African descent from the state. His words: “It would appear that the all-wise Creator has created the negro to serve the white race…If you would wish that all mankind should be free, do not bring the two extremes in the scale of organization together; do not bring the lowest in contact with the highest, for be assured the one will rule and the other must serve.”

For every image of the past that is not recognized by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably.11

Now it is 2020. The President of the United States recently gave a speech announcing the creation of a “1776 Commission” that will “restore patriotic education in our schools.” This “pro-American” curriculum, the President asserted, is meant to counter such alleged leftist “propaganda” as the New York Times 1619 Project— the widely acclaimed and Pulitzer-prize winning project that tells American History “by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of Black Americans at the very center of our national narrative.” Despite the richness and evident factual truth of this narrative, The President has described it as having “warped, distorted, and defiled the American story with deceptions, falsehoods, and lies.” In the President’s version, American History is “a miracle”– this is his actual word– and cannot be sullied.

So, of course, history is a tool.

The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the “state of emergency” in which we live is not the exception but the rule.12

Among the many stupidities that animate Trump’s malevolence, is the assumption that his history is somehow fixed and free of ideology. It is the truth. By this willfully blind account of the historical method, if you write a new history, bring hidden events to light, express different values about what should be memorialized, you are erasing something valuable and true, even magical. If you seek to deal with the repressed traumas of America, or provide any kind of critique, you are merely being negative, creating shame, tearing down.

Critique, in fact, is generative, or ideally should be. It is that process described above of moving from ostensible paranoia to repair. It is also a particularly important part of the American story. The American Revolution, and the many other revolutions that followed– the French and Bolivar’s liberation of South America certainly, but arguably all post-Enlightenment revolutions– were fed by the notion that humans can determine what is unjust, and, by the force of reason and the power of self-determination, establish governing principles of greater justice. This animating principle is not consumed in a single blast. If true to its own inner logic, the story goes, critique is the eternal flame guiding any truly democractic society, and that if extinguished will spell the end of freedom.

Compare in this regard Trump’s “Make America Great Again”13 to James Baldwin’s patriotic call, in the Fire Next Time, to “achieve our country.” Baldwin is one of the most vivid and penetrating voices we have on the impact of racism on American Life. In a famous debate with William Buckley Jr., he flatly declared: “The American Dream is at the expense of the American Negro… I picked the cotton, and I carried it to the market, and I built the railroads under someone else’s whip for nothing. For nothing.” This argument is echoed in the 1619 Project. Yet, Baldwin also fiercely defended the idea of America. “I love America more than any other country in this world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.”

In the Trump version of “America,” there was a mythic time of greatness– when exactly is never clear– a time of purity, presumably, that has been compromised and must be re-established. This is conservatism at its essence– a fight against time. Baldwin’s version of America, on the other hand, is an aspiration, a guiding principle that cannot be realized by ignoring the past or pretending it was something it was not. For him, there is no past innocent of the present; no present innocent of the past. The achieving of Baldwin’s America takes constant work and the drive to achieve also recognizes that this work is never done. Critique is always necessary, produced out of vigilance and a recognition of both our best and worst qualities. This is progressivism at its essence– a fight with time.

For some, this sort of progressivism is anathema because it is not sufficiently systemic and some want no part of any America. That is certainly understandable.14 Benjamin would have been one of those and this is one of his limitations in our view. For Benjamin, as for many now, the past can only be redeemed in complete revolution or some Messianic moment. The logic of Enlightened governance by critique is a sham, some hold, when clearly founded on racist ideology and the necessary creation of the frontier, the empty place, the ones to be exploited.

Richard Rorty warned against the risk of this position in an extended meditation on Baldwin’s version of an aspirational America titled Achieving Our Country. Rorty’s book is an extended argument for the positive value of critique within the American context. Rorty specifically addressed the Left in a way that anticipated the attacks of Trump, even in 1997 when the book was published.15 Rorty urged the Left to seize not only the moral high ground of truth telling about history but also to seize the initiative in expressing something collectively affirmative and aspirational, a story of our country that comes with concrete legislative objectives. This necessitates departing from Benjamin’s view of history that sees only a trail of violence. (Benjamin imagines a “Angel of History” and of this angel he wrote: “Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe, which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage.”). For Rorty, the historian of the Left, as distinct from Benjamin’s version of the Marxist historian, celebrates diversity and the legacy of multiple cultural achievements; sees hope in the American idea.

Ultimately, Wozencraft’s treaties were not ratified. Not because they were morally abhorrent nor because they were a processual farce, but rather because the United States Senate felt they actually granted too much gold-bearing and agriculturally-rich land to the natives. In a rare act of self-recognition, the Senate effectively argued, “What is the point? If we grant this land, the white men will eventually come take it anyway.”16

Yet, many of California’s indigenous nations survived and now have been formally recognized. Some land has been returned–not nearly enough, but some. The story of indigenous people is not just a story of the past, a story to be memorialized, but a story of the present, of diverse people, ordinary people, people with a political agency and a story to tell of their own history. Standing Rock is one chapter of that story that caught many people’s attention. In a cruel irony, Wozencraft’s morally bankrupt pieces of paper, blood-stained and shot through with racist ideologies, would actually have been a very useful tool in the twenty-first century for indigenuous nations in California asserting land and water rights. Standing Rock protests relied in part on similar treaties for its legal standing.

However, the continuation of indigenous cultures happens in many ways and in places that are not often captured by the media. Many Americans are not aware of the indigenous people and communities currently existing all around them. It was really by engaging with California history (including the image we started with) as part of our Water Gold Soil project that our understanding of our home in New York State deepened. The university where we teach is on the ancestral lands of the Onondaga and the flag of the Hausensonsee (Iroquois) Confederacy, of which the Onondaga were a part, flies on the campus.

Toolshed’s physical location at Basilica Hudson is on the ancestral lands of the Mohican or Muh-he-con-neok, meaning people of the waters that are never still. The history of the Mohicans is too long obviously to tell here, but after living along the Mahicannituck (Hudson River) for hundreds of years, they traded with Europeans when they came and fought on the side of the Americans in the Revolutionary War. However, after the war the Mohicans were forcibly removed from their lands and marched westward, ultimately settling in Wisconsin as the Munsee-Stockbridge Band of the Mohican Nation.17

One tool for raising consciousness, is called a land acknowledgement, wherein the history of the land as stewarded by the indigenous people is spoken and respected. This encourages people to research and come to know the people who lived in a place prior to colonization. This has the effect of transforming and stretching our idea of history. We first heard such a land acknowledgement in Australia where it is much more commonly a part of official events. Hearing this acknowledgement in a country to which we had flown thousands of miles in order to deliver a talk on the climate crisis (hypocrisy acknowledged), instantly and profoundly changed our understanding of where we were and what we were doing there.

The land acknowledgment that the Stockbridge-Munsee band of the Mohicans have developed is as follows:

“It is with gratitude and humility that we acknowledge that we are learning, speaking and gathering on the ancestral homelands of the Muhheaconneok, who are the indigenous peoples of this land. Despite tremendous hardship in being forced from here, today their community resides in Wisconsin and is known as the Stockbridge-Munsee Community. We pay honor and respect to their ancestors past and present as we commit to building a more inclusive and equitable space for all.”

These words, or words like them, are intended to be spoken before events or gatherings. It acknowledges the violent past and displacement of the Mohicans. It acknowledges the right of self-determination and the integrity of Mohican culture. But it is also inclusive, grounded in the present and inviting of collaboration.

There is a secret agreement between past generations and the present one.18

Notes

| ↑1 | Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” in Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schoken Books, 1968), 254. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The use of the word “paranoia” here does not indicate a pathology or any sort of permanent state. It is a state of mind (increasingly common) that grows out of what Paul Riceour calls the “hermeneutics of suspicion.” It is, in this usage, a “position.” Our understanding of paranoia in this sense is informed by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, who is, in turn, informed by Melanie Klein. Sedgwick glosses Klien in her seminal essay “Paranoid and Reparative Reading,” as follows: “For Klein’s infant or adult , the paranoid position-understandably marked by hatred, envy, and anxiety-is a position of terrible alertness to the dangers posed by the hateful and envious part-objects that one defensively projects into, carves out of, and ingests from the world around one.” |

| ↑3 | In the background here is an attempt to come up with a better lexicon for “knowledge” and “understanding.” There is in our society an unconscious bias towards forms of understanding that are entirely rational. Edouard Glissant productively distinguishes between understanding in the sense of grasping (in all its possessive, acquistive connotations) rendered by the French word comprender and understanding in more relational sense that does not have an appropriate verb in French or English. Glissant uses the neologism donner-avec to convey this sort of understanding. Betsy Wing translates Glissant’s donner-avec as to give on and with. We are using the word “to yield” here in the same sense. |

| ↑4 | Without question this knowledge is not held in the same way by all people with the same degree of intensity. Yet, it might be helpful to understand this knowledge as recently made more generally felt for reasons expressed, for example, by Achille Mbembe in several places– none more clearly than a recent Op-Ed (in the Daily Maverick on May 25, 2020), as follows: “Strictly speaking, racism is a structural, systemic way to render the world uninhabitable for some. It is one of the many ways in which the ecology of human relations is destroyed and the universal right to breathe curtailed for some. As such, the struggle against racism must become part of the broad struggle to repair the biosphere, to render the Earth alive again for all, fully fit again for co-constitution and cohabitation. We therefore have to reframe the terms of our struggle against racism in planetary terms, within the broader perspective of our ecological futures. Debates about how life on Earth can be reproduced and sustained, and under what conditions it ends are forced upon us by the epoch itself. The latter is not only characterised by the crisis of climate change, but also by technological escalation.” It bears emphasis that understanding what Mbembe calls in this connection, the Becoming Black of the World, in no way whatsoever denies that some are significantly more vulnerable than others, and that the intensity of this feeling of being pursued, even hunted, by the past is unevenly distributed in the extreme. How to redistribute that threat and the burden of living with it is one of the most urgent questions of our time. One might say the question. This essay is about how history can be a tool for answering this. |

| ↑5 | Walid Ra’ad, “Walid Ra’ad by Alan Gilbert” interview by Alan Gilbert, Bomb, October 1, 2002, accessed 10 July 2018, https://bombmagazine.org/articles/walid-raad/. |

| ↑6 | Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” in Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schoken Books, 1968), 255 |

| ↑7 | Peter Burnett’s State of the State Address in 1851 as found in Benjamin Madley, An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 186. |

| ↑8 | These numbers come from a table produced in Brendan C. Lindsay, Murder State: California’s Native American Genocide, 1846–1873 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012), 128. The numbers are estimates and vary, but there is no doubt about the extent of the genocide. |

| ↑9 | See Robert Heizer full text rendering of this and other of these so-called treaties, as well as his narrative account and withering critique of them in The Eighteen Unratified Treaties of 1851-1852 Between the California Indians and the United States Government, 1972, which is available on-line courtesy of the University of California, Berkeley. |

| ↑10 | This opens up another series of speculations: how was this grouping decided? Did it involve some process of negotiation? Did the photographer consider alternate arrangements of the full group, and reject them for any number of reasons? Who thereby disappeared from history. Particularly poignant in this regard is the work of the artist Wendy Red Star titled “1880 Crow Peace Delegation,” which, in the words of MASS MoCA where they are currently the work is currently on view, consists of “annotated portraits of the historic 1880 Crow Peace Delegation that brought leaders to meet with U.S. officials for land rights negotiations. Using red pen to add text and definition to the archival images, she draws attention to the ways in which the original portraits deliberately remove the leaders from their contexts.” |

| ↑11 | Benjamin, 255. |

| ↑12 | Benjamin, 257. |

| ↑13 | “Make America Great Again” did not actually originate with Trump. For example, Reagan and even Goldwater before him used the same phrase. It draws on “America First” sentiment that preceded Trump. |

| ↑14 | Baldwin argued, “Du Bois believed in the American dream. So did Martin. So did Malcolm. So do I. So do you. That’s why we’re sitting here.” Lorde countered, “I don’t, honey. I’m sorry, I just can’t let that go past. Deep, deep, deep down I know that dream was never mine.” This argument is a good summation of why someone might object even to Baldwin’s America, to say nothing of Trump’s. |

| ↑15 | From Achieving Our Country, p.89-90: “Members of labor unions, and unorganized unskilled workers, will sooner or later realize that their government is not even trying to prevent wages from sinking or to prevent jobs from being exported. Around the same time, they will realize that suburban white-collar workers — themselves desperately afraid of being downsized — are not going to let themselves be taxed to provide social benefits for anyone else. At that point, something will crack. The nonsuburban electorate will decide that the system has failed and start looking for a strongman to vote for — someone willing to assure them that, once he is elected, the smug bureaucrats, tricky lawyers, overpaid bond salesmen, and postmodernist professors will no longer be calling the shots.” |

| ↑16 | A representative quotation from the Senate deliberations: “The reservations of land which they (the Commissioners) have set aside…comprise, in some cases, the most valuable agricultural and mineral land in the State…They knew that these reservations included mineral lands, and that, just so soon as it became profitable to dig upon the reservations than elsewhere, the white man would go there…”, as found in Alan J. Almquist and Robert Heizer, The Other Californians: Prejudice and Discrimination Under Spain, Mexico, and the United States to 1920 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977), 77. |

| ↑17 | Connecting with the Mohicans and learning from them is a crucial part of Toolshed. We are working with Munsee-Stockbridge Director of Cultural Affairs, Heather Bruegl and Agricultural Agent Kellie Zahn. We are also advised on our project more generally by Professor Scott Manning Stevens who is our friend and colleague at Syracuse University. Scott is Mohawk. |

| ↑18 | Benjamin, 254 |