The first few times I mowed the grass around the ponds where I live, the mower cut more than just grass. I would feel a little thud as I went, and stop the machine to discover underneath the body of a large frog, shredded to pieces. It’d been sitting near the edge of the pond, as frogs do, and didn’t jump out of the way. Once, I could consider it a fluke. But after it happened twice, I started thinking about what I might do to keep it from happening again.

Slow down. Adjust down the speed setting of the self-propelled mower so frogs might have more time to jump out of the way. Be careful. Inspect more closely the grass ahead of the mower, to see the frogs in time to stop and relocate them. Warn them. Walk round the pond first and try to flush out any frogs before I come through with a giant spinning blade. Or all of the above. But all of the above don’t change much about the situation. They take the tool at hand, the lawnmower, for granted. They don’t see past what is literally right in front of me.

Other responses involve reconsidering the tool itself. Make pasture. Get goats or sheep or other ruminants to graze the grass instead of cutting it. Go manual. Cut the grass with a non-electric push mower or an antique scythe. My electrical utility purchases energy for grid-connected power through the state’s wholesale market, so the energy here comes, like most, from a mix of sources (in NY currently about 27% hydro, 25% gas, 15% nuclear, 32% from “dual” gas/petroleum facilities, and a little sliver of 2% from wind, solar, and other renewables.) Since plugging in doesn’t wash my hands of dirty energy, these options are appealing.

But all these most obvious adjustments share a problem: they take time. Like so many people, in order to stay afloat economically I can’t currently care for livestock, manually mow a few acres of grass, or slow down the process in other ways. The more I thought about it, that first and most obvious response, the speed adjustment on my lawnmower, seemed an apt metaphor for a larger, more fundamental problem of time: a mismatch of speeds.

Mismatch of Speeds

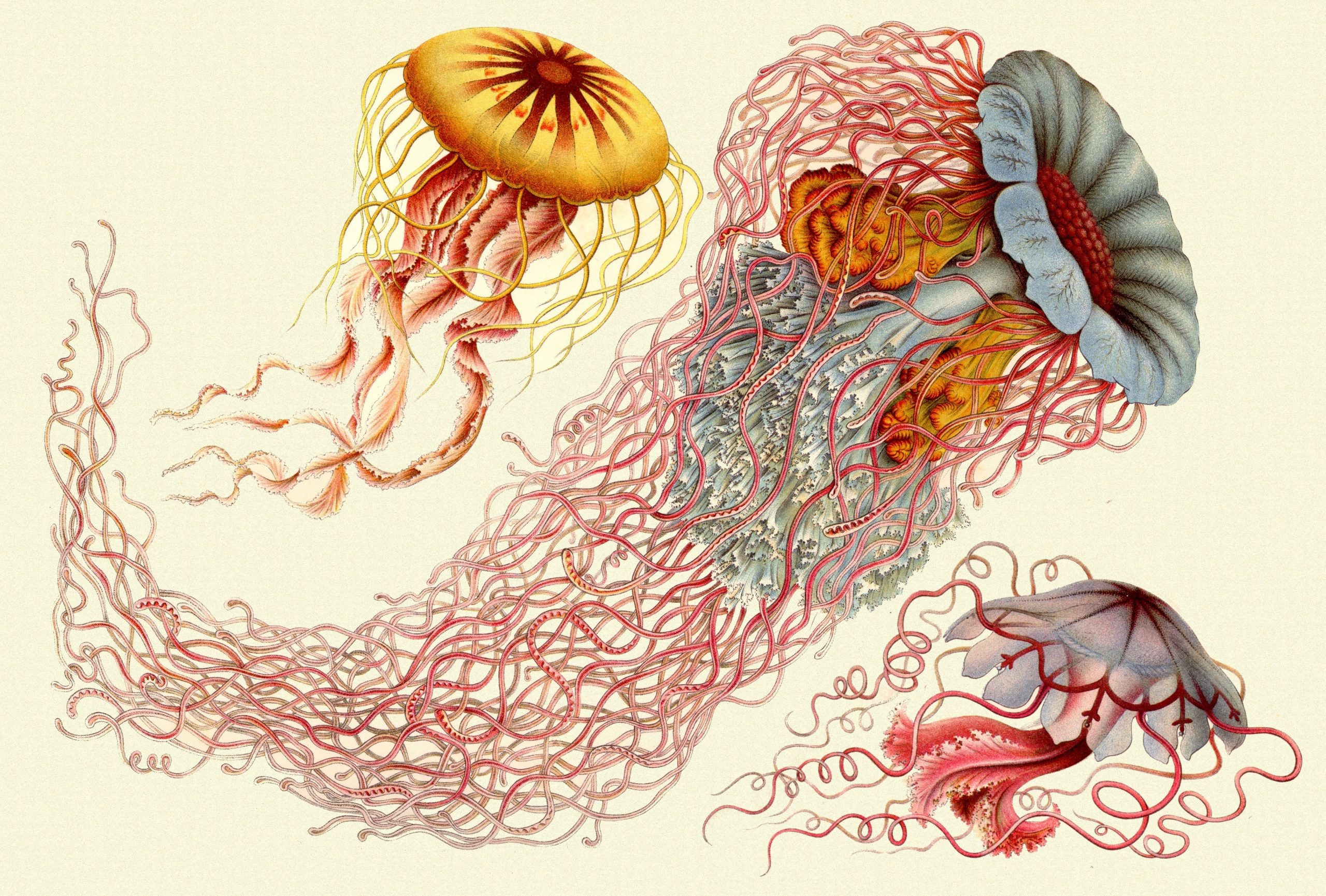

To elevate the problem to the level of a concept and coin a term, I’d like to propose pace ranae (pronounced “pah-chay rah-nay”), a suitably pretentious yet catchy term from the Latin for “speed of frogs.” Frogs are already considered an “indicator species” for so many environmental issues, and environmental discourse has a tradition of using frogs metaphorically to refer to the speed of cultural change via the spurious “boiling frog” parable. So frogs may be a worthy namesake for a mismatch of speeds in other contexts and scales.

Without getting too much here into the theory of speed (via academic concepts like dromology, timescapes, or immediacy, or debates around degrowth and accelerationism), what I mean by pace ranae might best be compared to the Marxian concept of a “metabolic rift” or differential processing of energy and material flows between class society and non-human ecologies. As one cause or effect of it, or one variant to do specifically with the movement of culture, and the ways time is constrained by economic pressures. In this seemingly trivial case, the pace of frog life seems out of sync with my lawn mowing.

The typical approach for a lawn of this size is to cut down on time and labor costs with a bigger machine, in reckless disregard for non-human life and anything else in its path. The people here before me hired a landscaping crew to cut the grass on riding mowers. These are so large and fast that the operator, perched high atop the machine and wearing protective earphones, is oblivious to the regular amphibicides they commit.

It’s an approach common to so much production and distribution in a capitalist economy: go faster, scale up. Usually this involves the use of fossil fuels that themselves embody a staggering mismatch of scale and speed, when viewed at geologic time scales.

The gallon of gas it takes to operate a riding lawnmower for an hour or two requires what once was 98 tons, or 196,000 pounds, of prehistoric, buried plant material. The coal, oil, and gas humans burn in one year requires as much organic matter to make as the entire planet grows in roughly 600 years.

One might think something larger and louder might actually scare frogs out of the path, but I wonder. See, frogs have their own options they seem to be considering, at different times or seasons, or perhaps according to species. When danger approaches, a frog’s general strategy seems to be to remain in place, stay as still as possible, and hope to go unnoticed. Which, conveniently, is also their strategy for hunting, or being a danger in their own right to other creatures in the food web. Often they will stay motionless in their spot until you get surprisingly close to them, almost touching, before they retreat by jumping into the water. If you try to creep up, it can begin to feel like a kind of contest between you and the frog or between the frogs themselves, as if they all have ongoing bets with each other about who can go the longest without flinching. Other frogs will let out a shrill cry before jumping, one that sounds not quite human but rather like internet videos of goats yelling like humans.

Challenging Our Culture of Speed

By not questioning the lawn itself, or my desire to maintain it, I was adopting a strategy like the frog’s, remaining motionless in the face of danger, even as it looms closer and closer. When I came into this land, I inherited the problem of maintaining it. And growing up in the culture I did, I inherited an expectation to see well-manicured lawns around houses. Agriculture, after all, from Latin ager ‘field’ + cultura ‘growing, cultivation’ is a kind of culture applied to land. The problem of pace ranae is as much one of culture as it is of the material conditions and technologies of grass-cutting. The problem is not the speed or schedule, but the fact of my mowing; not how or when, but that I mow in the first place. Put another way, it’s not just that I’m doing things too fast. It’s that I’m doing the wrong things. Pace ranae then becomes my name for the insufficiency, the privilege, and the danger, of merely slowing down.

The problem is not speed per se, but asynchrony between cultures. Not just the speed of culture, but the culture of speed.

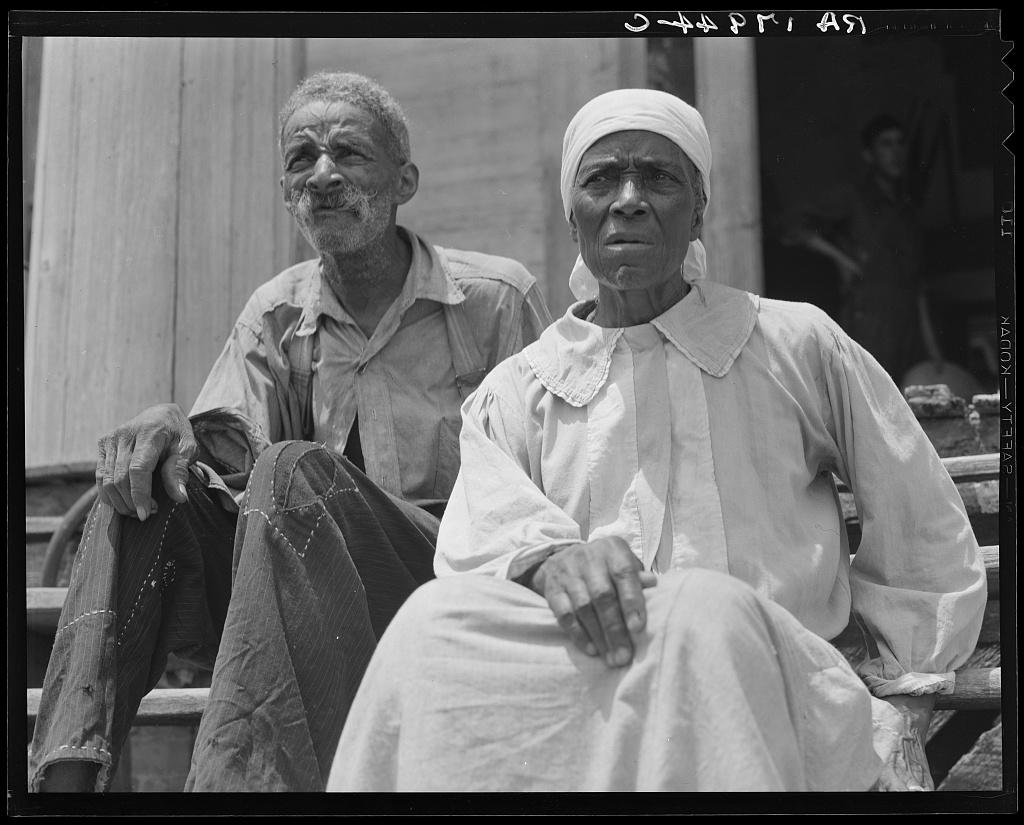

The frogs, too, have a kind of inherited cultural norm. Since this pond is spring-fed, it is likely that some small body of water has been here for many years. Frogs are known to return to their place of birth to breed, using a variety of visual, auditory, olfactory, and even celestial and magnetic cues. For them it’s habitual, if not instinctive. There is a community legacy here that far predates my own or other human use.

And there are other alternative community legacies to take into account. This land lies at the fuzzy border of the ancestral territories of three different native nations. It’s said to have been shared among them as seasonal hunting grounds. It’s a cruel irony that what some colonizers of this place appreciated as park-like landscapes of large trees with grassy understories resembling lawns were actually created by the peoples they were displacing, with a tool called fire and a culture of burning, both largely forgotten or still suppressed.

The easiest response would be to do“nothing.” Don’t overthink it. Let nature take its course. The unfit frogs will die and the species will be better for it. This approach is not only scientifically specious but also rhetorically suspect.

Calls for inaction can serve to mask action. The “do nothing” approach usually leaves out the fact that “something” is already being done.

Devoting the majority of land under my control to a monoculture of grass and maintaining it with petroleum-powered machinery is definitely doing something. Though it’s such a cultural norm that this massive intervention on the land seems like nothing.

Creating Symbiotic Ecosystems

What I decided to do, in the end, is something else. A mix of things, actually. For my yard, I let the grasses grow around the edge of the pond, broadening the natural “ecotone” or border habitat between water and terrestrial environments where diverse species find cover. I let some lawn remain, for the time being, for use in my composting, and for walking around the pond with less worry about ticks. But I’m slowly converting other grassy sections of the yard to pollinator gardens and other planting areas. With gradual adjustments, my vision is becoming less fixed to the conventions of “landscape”, and my presence more in step with the pace of the others that are here.

In the road next to my yard, I also started volunteering in the state’s Amphibian Migrations and Road Crossings Project, helping frogs, salamanders, and other amphibians cross roads during the critical Spring breeding season. What sounds like a cliche of Boy Scout do-goodism is actually an important service for conservation science, as participants also collect data on thousands of specimens, both live and dead. For dozens of species, it’s a real-life version of the classic video game Frogger, demonstrating quite plainly the difference in speeds between amphibians and automobiles. I like to think of it as a seasonal ritual, an intentional cultural custom to replace the many hollow holidays I inherit pre-inscribed into the calendar year. Together with hundreds of others across the state, we wait for the perfect warm rainy conditions known as “Big Night,” when countless creatures seize the moment to make their annual journey to ephemeral vernal pools. In an absurd choreography of safety vests and headlamps, we attempt to count them. And yes, sometimes help them cross the road.

In the process—sensing the weather, learning their routes—we become more attuned to place.

And in the community, beyond my yard, I also helped start a tool lending library called Toolshed Exchange. Unlike many tool libraries, our inventory does not include a lawnmower. Our decision not to stock one was intentional, as both a practical appeal to apartment-dwellers and a subtle cultural and infrastructural prod, encouraging our members to reconsider their land use, their speed, and their culture. There’s the old saying that with a hammer in your hand, everything looks like a nail. Without a lawnmower in our local tool library, maybe everything will start to look less like a lawn.

An idea is also a kind of tool.

Orthodox economists like Milton Friedman are wrong about a lot of things, but he was right when he said that when a crisis occurs, “the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes the politically inevitable.” In what is increasingly being referred to as a climate “crisis,” Toolshed Exchange is an idea of a real sharing economy, of commoning and re-commoming, that we’re trying to keep lying around, ready to be picked up and used. The tool library is part of a larger project called Toolshed, which functions in part as a kind of library for useful ideas.